William Blake said “you never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” I think about this ever-more frequently as the years fly by. I am at the point in my life where I want to “call it” when more than enough becomes maddeningly obvious. Enough of more than enough.

The latest episode in this series is the idea reported in the Des Moines Register and elsewhere that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE, or Corps) favors endangered species over people, especially with regard to the recent Missouri River flooding. I don’t claim to be an expert on the inner workings of the Corps, but I’ve been up and down the river enough times to know that this is not an agency staffed with radical environmentalists. I find this idea to be a crystallization of the obstacles before us as we try to make Iowa’s landscape more resilient, sustainable and ecologically sound.

Permit me to step back for a moment and take a look at this country’s history with the Missouri River. Although people all over the world identify the Mississippi as the American river, the Missouri is longer and drains a larger area (when you subtract the Missouri watershed from the Mississippi’s). From the continental divide in Yellowstone Park, a droplet of water travels 3,902 miles down the Missouri to the Mississippi at St. Louis, and from there finally to the Gulf of Mexico. That’s the world’s 4th longest river stretch and would be the longest were it not for the work of the USACE and others shortening both of the great rivers hundreds of miles to facilitate shipping and navigation. I challenge you to stand where Sacagawea stood with Merriweather Lewis atop the hills overlooking the start of the Missouri’s main course at the Madison, Jefferson, and Gallatin River convergence at Three Forks, Montana, and not be in awe of the natural grandeur of America. Or look at the lower falls of the Yellowstone River, the Missouri’s once awesome tributary, now sometimes sucked nearly dry by irrigation before joining the Missouri in western North Dakota. Imagine what this country’s great rivers were once like.

For the Missouri, everything changed with the Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944 that authorized management of the Missouri River basin for navigation, flooding, water supply, hydroelectricity and recreation. “Pick” was General Lewis A. Pick, head of USACE. Over 50 dams were constructed as a result, and the Missouri channel was straightened up to Sioux City to facilitate movement of barges. The largest earthen dam in the world (until 1975) was constructed on the Missouri at Glasgow, Montana and was actually finished prior to the Pick Sloan Act. Five more Missouri dams were constructed in the Dakotas: Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall, and Gavins Point. As part of this, 202,000 acres of Native American land were transferred to the USACE. Imagine the outrage today if 202,000 acres of Iowa farmland were ceded to the federal government.

Although many people would likely say the hydrological transformation of the Missouri basin benefitted the American economy, in my view it was also an unmitigated environmental disaster on par with the loss and degradation of the Florida Everglades. Most of the sediment transported by the Mississippi River came from a wild Missouri slithering back and forth across its erodible floodplain over the millennia. Trapping the sediment behind dams and divorcing the river from its floodplain largely ended sediment delivery, contributing to the erosion of coastal wetlands in Louisiana and imperiling species that evolved to use the unrestrained river and its floodplain. Furthermore, this transformation caused the Missouri to erode downward, destabilizing many of its Iowa tributaries in the Loess Hills area of our state. This has resulted in massive streambank erosion and water quality degradation of our own inland streams.

“Control” of the river helped populate the lower Missouri valley and make it into a highly productive agricultural area. In doing that, we followed in the footsteps of the ancients. Since the dawn of agriculture, our species has been lured by highly-productive floodplain soils, and in fact civilization arose in such situations in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Native Americans also used floodplain agriculture to obtain food security. Despite the risk of devastating floods, rich soil along with easy access to irrigation water from the river has been too tempting to resist.

In the present time, we clearly do not need to live and farm in the Missouri floodplain to achieve food security. That activity does arguably contribute to Iowa’s prosperity, but when things go wrong, boy do they go wrong, as the tragedies of 2011 and last month remind us. The thing that bothers me is that we refuse to admit that this tragedy is the result of periodic natural forces and instead blame human errors, especially, the errors of our government, specifically the errors of the USACE. When the Nile flooded the Egyptians’ land, did they blame Pharaoh? I don’t know, but I tend to doubt it.

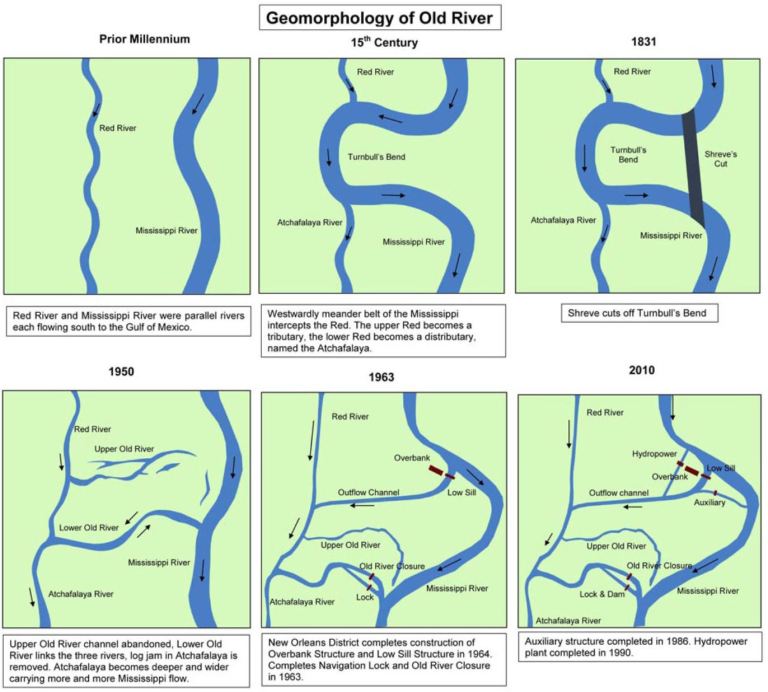

In the outstanding chronicle of the USACE effort to control the lower Mississippi River, Atchafalaya, John McPhee explored some of these ideas. McPhee describes how a bend of the Mississippi River near the Louisiana/Mississippi border flowed perilously close to the Atchafalaya River and actually started leaking water to the Atchafalaya about 500 years ago. The Atchafalaya is what is known in hydrology as a distributary. Following the huge 1927 Mississippi River flood, people began to realize that the great river might someday cast a wandering eye over to the course of the Atchafalaya, 10 feet lower and 150 miles closer to the Gulf of Mexico than the Mississippi’s current course. In such a circumstance, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and the American petrochemical industry would be left without a navigable river and the mouth of the Mississippi would be shifted 100 miles to the west. The laws of physics being what they are, the flow of the Mississippi is eventually going to be captured by the Atchafalaya. Such a course change happens once a millennia on average, with the last time being around A.D. 1000. In 1950, the USACE was ordered by Congress to preserve the current hydrologic condition of the Mississippi River forever by preventing such a natural calamity.

Now, I might say it is common for us to designate a motherly personage to nature. When it comes to hydrology, however, nature is not Mother. Nature is the father. A brooding, angry, and vindictive father. Drunk Dad, I will call him.

The USACE made the very bold decision to construct a control structure right at the spot where the Mississippi-Atchafalaya nuptials were most likely to occur. The resulting structure, completed in 1963 and called Old River Control, gently allows about 20-30% (but no more) of the Mississippi’s flow to detour away from the Mississippi main channel to the Atchafalaya and then to the Gulf at Morgan City, LA. Better to lose a managed 30% than lose it all. A blood-letting of sorts. Everything was copasetic until the Next Great Flood (1973), when Drunk Dad woke up with a hangover and was on the brink of taking the Corps to the woodshed. But, the structure held and the Mississippi remains in its 1950 channel today. An auxiliary structure was added after 1973 to bolster the system.

An interesting component to the McPhee tale is that seemingly everyone he interviewed (except Corps VIPs) expected the structure to fail at some point in the future. This included everyone from college engineering professors to the people sweeping the floor in the control room of Old River Control. They knew the Mississippi. At the time (1989), McPhee wrote: “People suspect the Corps of favoring other people. In addition to all the things the Corps does and does not do, there are infinite actions it is imagined to do, infinite actions it is imagined not to do, and infinite actions it is imagined to be capable of doing, because the Corps has been conceded the almighty role of God.”

A thousand miles north in Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and Nebraska, we also conceded what we thought was divine power to USACE, to break and tame the wild Missouri River. Not because we had to, mind you, but because we wanted to. How has that worked out for us? Well, sure enough, we did safeguard some good farm ground and urban infrastructure most of the years by having the Corps put the river in a prison. But shipping has been complete flop. In fact, not a single barge made the trip up to Sioux City from 2003 to 2014. I don’t know how you make the case that channelization was worth the resulting ecological disaster. Much of the shipping that has occurred in recent years has been to haul materials around to ironically create shallow water habitat for the endangered Pallid Sturgeon, in addition to some short-distance (<10 miles) movement of sands and gravels mined from the river for road projects. And as far as the flood? Well, in my view all this talk of bomb cyclones and climate change and endangered species is really a distraction from an uncomfortable idea: we have chosen to set up shop on a precarious piece of real estate.

We’re angry, but not because we wrecked of one earth’s great rivers. No, we’re mad because every once in a while, Drunk Dad gets to missing his rowdy teenage son Missouri, and busts him out of the prison the Corps built just for him, and then the kid goes on a crime spree. And despite our displeasure with the Corps, I have little doubt that we will ask them to bring the wrath of God down on the Missouri River, and call on them to build an even bigger and tougher and meaner prison. Such is our wisdom.

And that’s more than enough for now.