You may have heard that another lawsuit concerning the Raccoon River was dismissed by the Iowa Supreme Court. This latest one, pink-slipped in a 4-3 decision, was filed by Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement and Food and Water Watch. They asserted that the State of Iowa had violated the public trust doctrine, meaning the citizens of Iowa conveyed stewardship of our shared natural resources to the state and the state failed to fulfill the obligation with regard to the Raccoon River. The groups asked that the state create a mandatory remedial plan that would reduce nutrient pollution and ban new CAFOs in the watershed until the plan was implemented.

I’m not an attorney and I write this not to comment on the legal merits of the decision. Rather, I thought some dot connecting might be helpful to some readers and so that is my objective here.

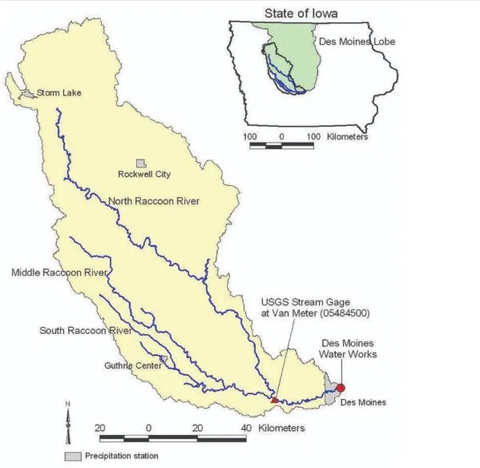

The watershed drains 2.3 million acres of land (approximately 6% of Iowa) lying northwest of Des Moines. More than 75% of the area is cropped and there is intense livestock production in the upper reaches of the basin. Much of the western and southern extent of the watershed traces the edge of the Wisconsin glacier, and melting ice created lakes along this edge, most notably Storm and Blackhawk Lakes, 10,000 years ago.

The southern edge of the advancing glacier bulldozed grapefruit-sized rubble to the present-day Raccoon River valley in Polk and Dallas Counties. Torrents of glacial meltwater covered the rubble with sand, creating a one-in-a-million, Goldilocks (just right) alluvial aquifer where sand-filtered river water was easily extractable from the buried rubble. Engineers constructed a clever groundwater collection system giving Des Moines perhaps the safest pre-World War II drinking water of any big city in the United States. While thousands died of cholera contracted from drinking bad water at the turn of the last century, Des Moines was left unscathed thanks to rocks and ice.

Yield of water from the groundwater collection system couldn’t keep up with post-war population growth, and the Des Moines water utility started drawing water directly from the river in the late 1940s. Not long after that, cropping systems all over the corn belt underwent a transformation which saw the adoption of the current all-cash-crop-all-of-the-time scheme which reduced plant diversity in the Raccoon watershed and increased the use of chemical fertilizers. This resulted in regular contamination of the river and the alluvial aquifer with nitrate. Awareness of the problem increased in the 1970s, concurrent with enactment of the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974). The utility began removing nitrate from the treated water in 1992, and a few years later received a grant from EPA to conduct monitoring and public engagement activities to raise awareness of the need for better water quality.

There’s been plenty of posturing and grandstanding over Raccoon River water quality since then, but at times there seemed to be reason for optimism. There did appear to be some pause in the increase of nitrate levels in the 2000-2010 period, but the pollution came roaring back after the 2012 drought and the worst nitrate years have occurred since then. This ominous cloud is about the only cloud hanging over Iowa during this current drought year, and there likely will be very bad news when the rains return. But despite the occasional ray of hope that happens to appear every few years or so, looking back, I have to say the watershed has probably been a lost cause for quite a while now.

In 2010, Iowa DNR received funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to develop a water quality master plan for the watershed. Stakeholder organizations sent representatives on a week-long retreat to help provide information and expertise to develop the plan. I was one of those people. A plan was developed and posted for public comment. Iowa Farm Bureau Federation commented thus: “IFBF asks the final master plan focus on implementation options that recognize (the) right of watersheds to develop a voluntary plan of action to address the agricultural nonpoint source issues, that support ongoing water monitoring and science development, and avoids numeric targets for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment or regulatory actions affecting fertilizer applications or other farmer management decisions.”

Consider that comment Mission Accomplished.

Paraphrasing Matt Damon in The Martian, the scientists are going to science the shit out of this baby (currently about 2000 scientific journal articles at least mention the watershed). The human genome may have been mapped in 13 years, but evidently that is child’s play compared to sourcing Raccoon River pollution to its origin. Various groups are going to continue monitoring the river and its tributaries, and DNR and EPC will continue ignoring the data so they can cowardly avoid establishing numeric water quality targets. Farmers continue to have license to apply as much fertilizer as they wish and in the manner that suits them, and people in the upstream watershed WILL recognize their right to develop (or not develop, as the case may be) voluntary plans of action.

I know some will hate this paragraph, but I think it needs to be said. Over the past 20 years, the ag establishment and the watershed’s farmers have made a mockery of efforts to improve the drinking water source serving 1/6th of Iowa’s people, and Iowa’s appointed and elected leaders, including supreme court justices, have for the most part endorsed this. Supported by Iowa’s economic and political establishment, the larger body of the watershed’s farmers have no intention of trying to reduce nutrient pollution, and this has always been so. I’ve seen firsthand on many occasions the hostility to change, and this was before both lawsuits. I’m not stating this as a casual observer.

I do see an upside to all this and that upside is that agriculture has, whether they like it or not, claimed the stream for their own. The people that say they hate finger-pointing have shown us their middle finger, and in doing so have told the world who’s to blame for the water in the Raccoon River.

It’s all yours boys.

___________________________________

What follows is an analysis of the recent lawsuit decision. This was written by Neil Hamilton, Professor Emeritus of Agricultural Law and former Director of the Drake Agricultural Law Center at Drake University. I’m including it here with his permission.

Iowa Supreme Court Rejects Public Trust Doctrine challenge on Raccoon River water quality

Prof. Neil D. Hamilton, June 18, 2021

In a closely decided 4-3 split ruling the Iowa Supreme Court rejected a case filed by Iowa Citizens for Community Action and Food and Water Watch alleging the state of Iowa failed to protect the interests of the public in the Raccoon River. The case involved an appeal from the district court rejection of the state’s motion to dismiss the case. The majority ruled the district court’s decision should be reversed and the case dismissed, concluding the plaintiffs do not have standing to bring the suit and their effort to use the public trust doctrine to establish the duty of state officials is a “nonjusticiable political question.” The majority’s ruling and analysis generated three separate dissenting opinions, all agreeing the case should move forward, in large part because the state had conceded the plaintiffs had standing and the merits of the public trust doctrine were not in question.

A reading of the majority opinion shows it was premised on a determination by the four justices to not involve the Court in the difficult and controversial political issues involving water quality in Iowa. This motivation was demonstrated in at least four ways:

First, the majority used a new and somewhat strained interpretation of standing, involving tests not previously applied in Iowa from a federal case neither side had argued, to find the plaintiff’s claims did not show adequate causation and were not redressable. It reached the conclusion even though the state had conceded the plaintiffs had standing

Second, the majority rendered a narrow interpretation of the scope of the public trust doctrine, focusing on river access rather than the broader and accepted inclusion of recreation, even though the state had not challenged the plaintiff’s claims how the doctrine applied in the case.

Third, at several points the majority said the merits of the plaintiff’s claims were not before the Court, but it spent over ten pages of the ruling essentially considering the merits and possible judicial outcomes, to ultimately conclude the case involved nonjusticiable political questions. As Justice Oxley said in dissent, “That the majority has decided the merits of the public trust issue is best seen in its discussion of the political question doctrine” explaining how it was not persuaded by the plaintiff’s showing.

Fourth, the majority ruling dismissing the case was described by the dissenters as being premature. In the words of Justice Appel, the newly discovered elements of standing were “astonishingly applied at the motion to dismiss stage of litigation to dismiss cases involving important state constitutional issues.”

Justice Mansfield made a concluding comment which may crystalize variations in judicial philosophy, writing: “In the end, we believe it would exceed our institutional role to “hold the State accountable to the public.” Those words, used by the plaintiffs to describe what they ask of us, go beyond the accepted role of the courts and would entangle us in overseeing the political branches of government.” Some observers might ask if it is not the role of the Iowa Supreme Court to hold the State accountable to the public then who does have that role?