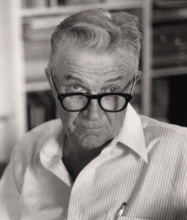

Texan John Graves (1920-2013) might be the best writer you’ve never heard of (unless you have) and I can tell you in his hands the English language was like a basketball in Michael Jordan’s. Not only did he make it do stuff that you didn’t know was possible, his words make you feel things you didn’t know you could feel. If Goodbye to a River isn’t the best book of its kind ever written, I’ll drink a straight up gallon of any Iowa river after a springtime gully washer.

It wasn’t Goodbye that inspired this essay, but rather his essay Cowboys: A Few Thoughts from the Sidelines. Graves grew up when the legendary Texas cowboy of old was still a thing, riding the range, ropin’, fencin’ and castratin’ for months at a time without a day off, sleeping under the stars and wolfing down food as it became available, earning meager wages that were squandered getting drunk on whisky and a hooker really frisky.

A myth developed around these hard fellows that the country and even the world fondly embraced, a myth that still persists today, even though the real McCoy cowboys haven’t existed since the years immediately after World War II, when barbed wire and the economic realities of feedlot beef conspired to cancel the occupation. Certainly many of the real cowboys were an embodiment of courage and hard work, virtues this country, rightly or wrongly, considers supremely American. And as such, many in the public emulate the cowboy wardrobe and other aspects of their appearance and demeanor, something Graves tells us was uncommon during the real cowboy era.

But Graves also tells us that myth and truth entangle in ways that confound our thinking and cause us to misjudge the cowboys’ motives and conduct, despite the lofty ideals that many of them had toward hard work, determination and loyalty. And as the title here gives away, this got me to thinking about the myth of the Iowa farmer and how it affects our thinking about the occupation today.

The 40,000 full time and similar number of part time Iowa farmers are outnumbered by several professions, including frequently vilified teachers, but yet we’ve made farmers the soul of the state. We’re asked to thank them at every turn and we groom our school children to hold them in the highest regard (1). We bestow favorable tax policy upon them along with public money to bolster and indemnify their operations. We bless the damage their overweight vehicles and equipment impart to our roads and bridges and most aggravating, turn a blind eye to their pollution.

Our politicians swoon like teen age girls when these barnyard Beatles take the stage, and in unity with them don the phony pharmer chic of denim and flannel, pro-wrestling-sized belt buckles, and boots. Especially boots—not shiny new Tony Lamas, but scuffed square toed shit kickers that track dust and manure crud and cred across every carpet they touch, just so you’ll know their veins course with farmer blood and their feet are caked with dirt road mud. It’s almost like John Travolta and Debra Winger were running our state. Years and beers may have made my memory a little hazy these days, but I sure don’t remember Harold Hughes and Bob Ray (Iowa governors from Ida Grove and Des Moines in the 60s and 70s) acting like this, back when real farmers didn’t ask the public to fawn over them, and we weren’t required to put a salve on their festering insecurities with buffoonish ‘feed the world’ and ‘god made a farmer’ baloney.

(It did come to me that Hughes may have worn a bolo tie with a flannel shirt in public once in a while.)

It's interesting that the myth of the Iowa farmer has grown inversely with the level of their toil and travail but in lockstep with their wealth and the number of paid mythmakers that loiter around the industry like barking hyenas. Like Graves and his cowboys, I have some fond remembrances of Iowa and the Iowa farmer that existed in my childhood and before. But over the last 40 years, the myth has become ever less objectively based and the myth creation ever more sophisticated, which I suppose is necessary because it exists almost solely on nostalgia and the power of propaganda.

I hear people in agriculture decry the public’s ignorance of the trade and the industry, but at the same time they project images of farming that only rarely still exist—agrarians hardened by weather and worry managing diverse farms with modest outdoor animal populations. It’s no wonder they need the mythmaker army when the truth is something so altogether different.

But perhaps I’m too harsh. Maybe I should let go, embrace all the myths about Iowa agriculture managing the impossibly complex task (for mortals, anyway) of being the world’s first environmentalists while at the same time feeding, fueling and fibering the entire world, and thus I feel, for only a moment, that I should join the masses in thanking Iowa agriculture and its farmers. So here goes.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for allowing us to have 1576 square miles of public land, half of which is in road right-of-ways. Our percentage of public land (2.8%) is an enviable 48th-most of any state, a number that is sure to entice our young people to remain here and forgo miserable outposts like Minnesota, Colorado, and Oregon.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for leaving us 15 stretches in 70,000 miles of streams that meet their Clean Water Act designated uses. That’s one good stretch of river for every 200,000 Iowans—not bad! Take that, Rhode Island!

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for helping to eliminate only 720 million grassland birds (61% of them), just in the span of my life (2). I used to see meadowlarks as commonly as robins in town when I was growing up and now through the good graces of Iowa agriculture I might see a couple or three on a two-hour drive across the Iowa countryside. And thank you agriculture, for waiting until my quail-hunting grandad died before making the bobwhite scarcer than hens’ teeth.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for showing us how foolhardy it was to construct several dozen lakes across the state, all at taxpayer expense. We should’ve known your sediment and nutrients would make these cauldrons of green stew, so please forgive our ignorance on that. We’ve learned our lesson and won’t make the same mistake again in the future.

Thank you, Iowa and U.S. agriculture, for graciously accepting our $300 billion spent since 1936 (in adjusted 2009 dollars) (3) so you could try to stop losing your soil to erosion. Soil loss in Iowa averages 5.4 tons per year (4), still above the USDA threshold for ‘sustainable’, but, good try. We still have some checks left in checkbook.

The owners of 55,000 tested wells that have not been contaminated with nitrate to unsafe levels thank you, Iowa agriculture. The owners of 6600 others that have been contaminated wish to say they fully understand and know that you would never, ever prioritize your crop yield over the safety of your neighbors’ drinking water, and that the contaminated wells are just an unfortunate circumstance of a golf course being located in the next county.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for allowing us to keep 30,000 of the original 7,600,000 acres of wetlands (20% of Iowa) that were home to countless waterfowl and other birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals and insects. And we’re eternally grateful for the 5,000 of the original 3,000,000 acres of prairie pothole wetlands that have been left to remain on Iowa’s Des Moines Lobe. We know it’s been a tough job laying drain tile on every last wet spot, but by god, you got the job done! If the remaining wetland birds could thank you also, I’m sure they would.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for letting us retain 0.1% of our native tallgrass prairie ecosystem. Sure, it helped that a lot of this was in pioneer cemeteries but let’s just be honest, corn could grow there, and you guys were nice enough to leave our great-great grandparents to rest in peace where postage stamp sized prairies could survive.

Thank you, Iowa agriculture, for leaving at least some of our streams in eastern Iowa unstraightened, and thank you for polluting the straightened ones in western Iowa to such an extent that it’s impossible for anyone alive to have any nostalgia about what they once were.

Thank you to all the aggressive tillers out there that are willing to accept our tax dollars for wind breaks to slow erosive winds. Yes, we know that laws banning mindless practices like fall tillage would be more effective and cost us nothing, but buying things like wind breaks helps us feel like we are part of the action, and helps us understand the forces you deal with.

And thank you, Iowa agriculture, for graciously accepting our funds to create pollinator habitat for the monarch butterfly, driven to the brink of extinction at least in part by your farming practices. After all, who could’ve predicted that all those years of ditch mowing and herbicide drenching would have negative consequences.

I had hard time knowing how to finish this one, so I’ll let Graves do it. He said that, like art, “Myth can influence the direction of human life, and may even influence its live subject matter if the timing is right. The popular cowboy myth was not shaped for cowboys, but a non-Western public who seized on it. But it reached real cowboys as well, and they seized on it too.” Can it be possible that this hasn’t happened here in Iowa? It surely has. The industry and its practitioners would have us believe that these heroes need our help and crave and deserve our admiration, and above all, need us to overlook the negative consequences of their actions. Of course without the myth and the mythmakers, we might be less inclined to do that last thing.

- Elliot, E. Students Learn That ‘Three Times A Day You Need A Farmer’. Harlan (IA) online.com, October 7, 2022.

- North American Grasslands & Birds Report. Audubon Society. https://www.audubon.org/conservation/working-lands/grasslands-report.

- Villarini, G., Schilling, K.E. and Jones, C.S., 2016. Assessing the relation of USDA conservation expenditures to suspended sediment reductions in an Iowa watershed. Journal of environmental management, 180, pp.375-383.

- Eller, D. Erosion estimated to cost Iowa $1 billion in yield. Des Moines Register, May 3, 2014.